Quick Bite – The Incredible Spend on AI

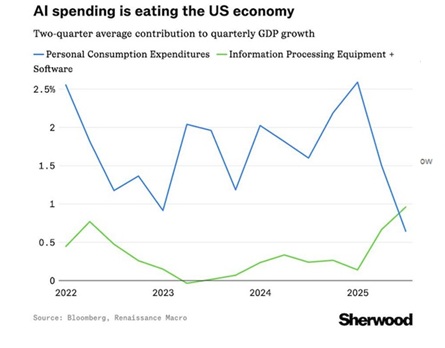

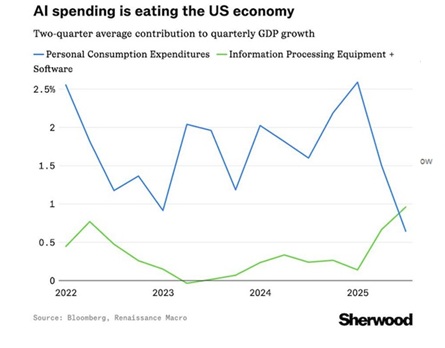

The US Q2 reporting season is revealing the enormous sums being spent on Artificial Intelligence strategies by the Big Tech giants. AI, and the chips, data and energy required to service it, are producing an economic stimulus strong enough to distort the economic data for the US and have fundamental long term consequences for the global economy.

The biggest companies in history are spending stunning amounts of money to fuel the AI revolution, driving demand for more chips, more energy and more capital. This dynamic is so vast that it is powerful enough to provide cover for a US economy that otherwise looks like it is slowing down.

The big dogs in this space (Nvidia, Microsoft, Apple, Alphabet, Amazon and Meta) are getting bigger, and putting more into direct investment and ownership of the products feeding into their AI.

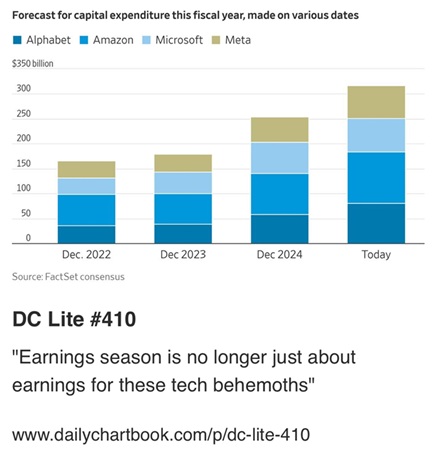

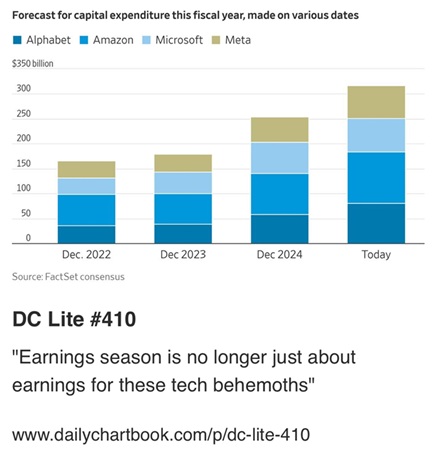

Source: DailyChartBook

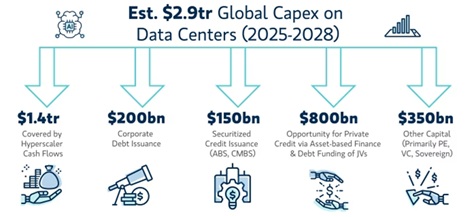

Big Tech is buying up land, building data centres, purchasing huge volumes of chips, and investing in new energy sources including small nuclear energy.

Microsoft, Amazon, Apple, Alphabet, Meta, and other major tech companies are investing heavily in data centres, particularly “hyperscale” data centres that are not only massive in size but also in their processing capabilities for data-intensive tasks such as generating AI responses. A single hyperscale data centre can consume as much electricity as tens or hundreds of thousands of homes, and there are already hundreds of these centres in the United States, plus thousands of smaller data centres.

In just the past year, US electric utilities have nearly doubled their estimates of how much electricity they will need in another 5 years. Electric vehicles, cryptocurrency, and a resurgence of American manufacturing are sucking up a lot of electrons, but AI is growing faster and is driving the rapid expansion of data centres. A recent report by Goldman Sachs forecasts that data centres will consume about 8% of all US electricity in 2030, up from about 3% today.

The interest in nuclear energy is largely due to AI. US electric utilities are forecasting the nation will need the equivalent of 34 new, full-size nuclear power plants over the next 5 years to meet power requirements that are rising sharply after several decades of falling or flat demand.

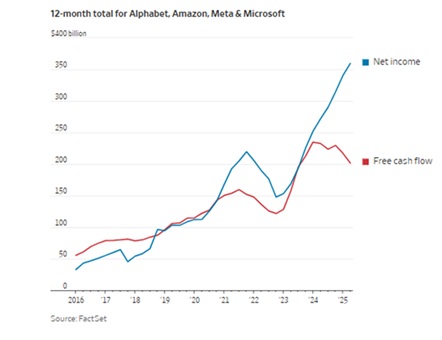

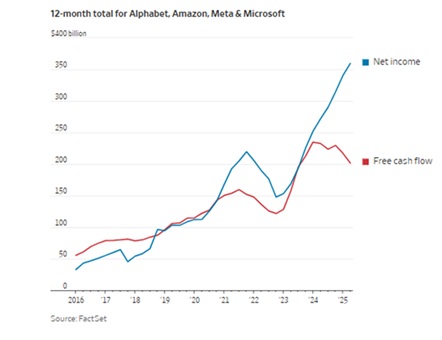

Where’s the Free Cash Flow?

To date, the market is rewarding this capex spend, but some are starting to ask when the return will come. “Show me the Money!” In the meantime, Microsoft and Nvidia together are worth about $2.5 trillion more today than they were a year ago.

For years, investors loved tech companies because they were “asset-light.” They earned their profits on intangible assets such as intellectual property, software, and digital platforms with “network effects.” Adding revenue required little in the way of more buildings and equipment, making them cash-generating machines.

This can be seen in the metric “free cash flow”, defined as cash flow from operations minus capital expenditures. This is arguably the purest measure of a business’s underlying cash-generating potential. Amazon, for example, tells investors: “Our financial focus is on long-term, sustainable growth in free cash flow.”

Free cash flow declining for Alphabet, Amazon, Meta and Microsoft

Source: FactSet

A small number of companies — some nearly the size of Germany’s economy — are spending more than the 340 million American consumers, whose status as the engine of the US economy has always been recognised.

Source: The Felder Report

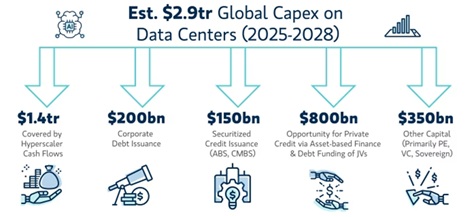

The massive amount of money being poured into these projects by Big Tech represents “an extraordinary challenge and a gamble.”

To understand just how big a challenge this is, the Financial Times reports that “America needs to find an extra 45GW for its data farms… equivalent to about 10% of all current US generation capacity, or 23 Hoover Dams.”

Source: FT

The AI-capex cycle has been around for a few years now, rising from ~ $125bn two years ago to ~$200bn in 2024, and expected to exceed $300bn in 2025. So far, internal cash flows from Big Tech companies have been more than sufficient to match these requirements, but there are profit consequences, with margins reducing.

Source: FT

Sceptics ask, “What about the risks around overbuild and obsolescence? What about the risk that cheap smaller-language-models like DeepSeek gut the corporate market, or that consumers’ willingness to pay never catches up with compute costs? What if compute becomes as commoditised as bandwidth did in the early 2000s? Who’s to say that when data centre securitisations come up for refinancing in a few years, vacancy rates won’t be higher?”

Source: Evans & Partners

These are appropriate questions to ask, and it is too early to be sure that all these companies know the answers. In the meantime, investors seem content to stay at the ball and continue dancing. But it’s hard to know when the music stops … until it stops.