Quick Bite –Migration Policies Increasingly Contentious (Part 1)

Migration policies in Australia are becoming political dynamite – you don’t need to see Pauline Hanson dressed in a burqa in the Senate to realise that. I’ll attempt to avoid political contention and focus on relatively well established facts to provide readers with some insights and information that largely emphasise the economic consequences of migration policy.

This edition of Quick Bites will be in 2 parts, because its length is significantly larger than usual. This is Part 1, and we will publish Part 2 in the following day or so.

The question is: What should Australia’s migration policy be? What is the long term plan? Can our leaders, be they political, business, academic or community leaders, agree on a sensible strategy that will deliver the best outcomes and minimise the potential pitfalls?

Historical background

First, some background: Australia’s migration story is a long arc from penal colony to one of the world’s most open labour markets. As we are familiar with, the first large-scale (non-indigenous) arrivals were British convicts in the late 18th and 19th centuries.

Free settlement accelerated in the 19th century and mass migration after World War II reshaped Australia’s demography and industrial capacity. The dismantling of the discriminatory “White Australia” policy from the late 1960s onward opened the country to greater geographic diversity, producing today’s 27.5 million multicultural population, workforce and consumer base.

Source: Voronoi

International migration has expanded at a remarkable pace over the past 35 years. As economies globalized and mobility increased, more people moved across borders for work, safety, and education. The chart above tracks how the share of foreign-born residents has changed across advanced economies since 1990. The data for this visualization comes from the United Nations.

Countries With the Highest Migrant Shares

Switzerland, Australia, and New Zealand show some of the highest migration shares among advanced economies. Each has seen steady increases since 1990, driven by strong labour demand and open migration channels. Smaller economies like Iceland and Austria also experienced rapid growth, transforming their demographic landscapes.

Spain, Turkey and South Korea illustrate how quickly migration patterns can shift. Spain saw one of the steepest increases, rising from just 2% in 1990 to over 18% today. South Korea’s share climbed from near zero to 3.5%, reflecting its shift to a high-income economy attracting foreign workers.

Countries like the US, Germany, Canada and the UK remain top global destinations based on total migrant populations. While their percentages have grown more gradually, their large base populations make them central to global migration flows. These economies continue to rely on international labour to fill workforce gaps and support long-term demographic stability.

Let’s focus on Australia – Pros and Cons

Economic advantages of migration for Australia are substantial and well documented. Migrants expand the labour force, fill skills gaps (especially in health, construction, IT and aged care), raise GDP and slow the impact of an ageing population by broadening the tax base and supporting public services.

Where do Australia’s Migrants Come From? (last 10 years)

Source: ABS

Government analysis shows migration’s contribution to future GDP growth and workforce participation, and Treasury modelling suggests positive long-run fiscal contributions from permanent migrants when integrated into the labour market. For financial markets and corporate balance sheets, migration supports labour availability, keeps unit labour costs under control in high-demand sectors, and supports consumption growth in housing, retail and services.

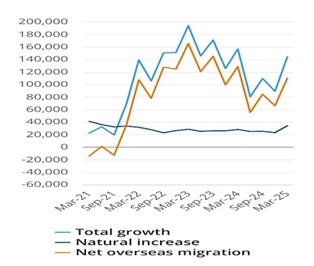

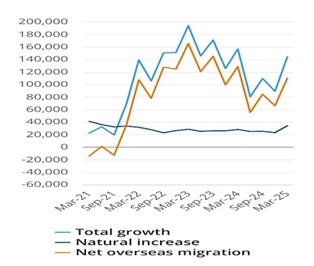

Australia’s Sources of Population Growth

Source: ABS

Criticism of high migration

Critics of high migration levels raise legitimate social, macro and microeconomic concerns. Social harmony can become strained if many migrants do not seek to integrate into mainstream society or do not share values that most Australians would regard as fundamental. Multiculturalism is one thing; wholesale rejection of so-called “western values” – things like democracy, gender equality, freedom of religion and expression, an independent judiciary, protection of minorities, participation in the workforce, and the rule of law (to name a few) – is something else entirely.

At a macro level, rapid net overseas migration can temporarily exceed the capacity of housing supply, transport and utilities — contributing to short-run inflationary pressure in rents and house prices, and straining public capital budgets if infrastructure lags.

At the micro level, concentrated inflows (e.g. in particular sectors) can exert downward pressure on wages in localised niches and increase competition for entry-level jobs. The gains from migration (higher aggregate GDP and productivity) are not identical to immediate improvements in median household living standards unless accompanied by adequate investment in housing and training. Some evidence shows migration interacts with housing supply constraints — critics argue a high intake exacerbates affordability problems when supply is rigid.