Quick Bite – Are Excessive Super Funds Giving Australia “Dutch Disease”?

Dutch Disease explained

Dutch Disease, coined following the Netherlands’ natural gas discoveries in the 1960s, describes an economic phenomenon where a resource boom paradoxically weakens a nation’s broader economic competitiveness. The mechanism operates through two channels: the spending effect, where increased income from the booming sector drives up domestic prices and wages, and the resource movement effect, where capital and labour shift from manufacturing to the resource sector. The result is an appreciated currency that makes tradeable goods sectors—particularly manufacturing—internationally uncompetitive, leading to premature deindustrialization.

The Superannuation Leviathan

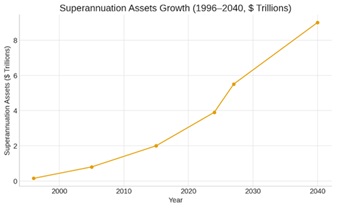

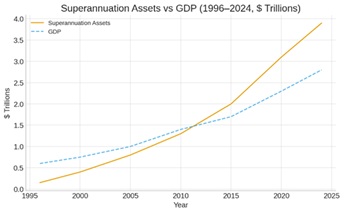

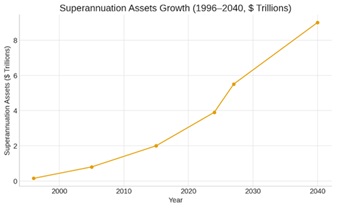

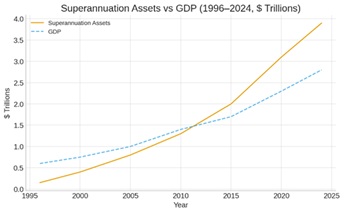

Australia’s compulsory superannuation system has created an investment behemoth of staggering proportions. As of September 2024, total superannuation assets reached approximately $3.9 trillion, representing roughly 140% of Australia’s GDP. This figure has grown exponentially from $148 billion in 1996, demonstrating a compound annual growth rate exceeding 12% over nearly three decades.

To contextualize this scale: Australia’s superannuation pool is the fourth-largest pension market globally, behind only the United States, United Kingdom, and Japan—nations with populations 13x, 2.6x, and 5x larger respectively. On a per capita basis, Australia’s $150,000 per person in retirement savings dwarfs comparable economies.

The system’s growth trajectory remains formidable. With the Superannuation Guarantee rising from 11% to 12%, and an ageing population entering peak accumulation years, industry projections suggest assets could reach $5.5 trillion by 2027 and potentially $9 trillion by 2040.

Capital Deployment and Market Distortions

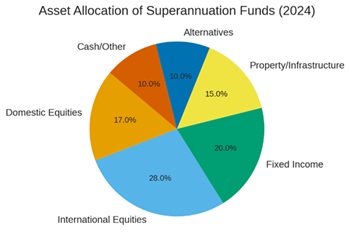

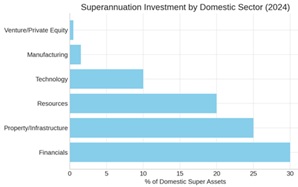

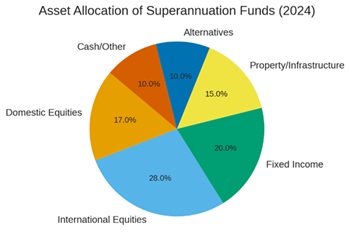

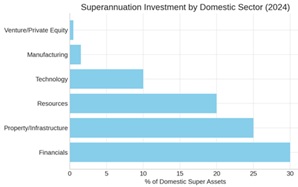

Australian superannuation funds deploy capital across diversified portfolios, but their sheer magnitude creates structural market impacts. As of 2024, approximately 45% of superannuation assets are invested in equities—roughly $1.75 trillion. Of this, domestic Australian equities make up approximately $600-650 billion, while international equities account for $1.1-1.15 trillion.

Domestic Equity Market Inflation

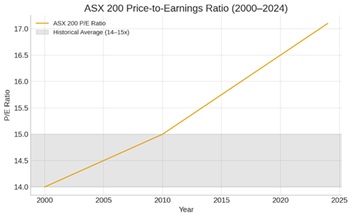

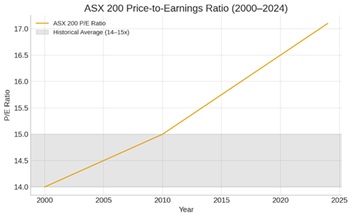

The ASX’s total market capitalization stands at approximately $2.6 trillion, meaning superannuation funds own roughly 25% of the entire Australian equity market. This persistent, mandated bid has compressed risk premiums and inflated valuations beyond fundamental justifications. The ASX 200’s price-to-earnings ratio has averaged 17-18x over the past five years, elevated compared to historical averages of 14-15x prior to 2010. At present, the forward PE is 19x, close to the top of its historic range.

Index concentration exacerbates this distortion. The Big Four banks and major miners represent approximately 40% of the ASX 200 by market weight, creating a feedback loop where superannuation inflows disproportionately inflate a narrow subset of large-cap stocks, regardless of underlying business conditions. We have observed this most recently with the pricing of Commonwealth Bank shares, which hit a peak of $192, pricing them well above virtually any comparable bank in the world.

Currency Appreciation Dynamics

The superannuation system’s offshore investment component—approximately $1.1 trillion—requires initial AUD conversion, but subsequent repatriation of dividends, distributions, and rebalancing flows creates ongoing upward pressure on the Australian dollar. Australian funds have become significant owners of global equities, with estimates suggesting they hold $150-200 billion in US equities alone.

With the boom in Artificial Intelligence mega-cap stocks in the US, our super savings are highly vulnerable should the AI boom eventually burst.

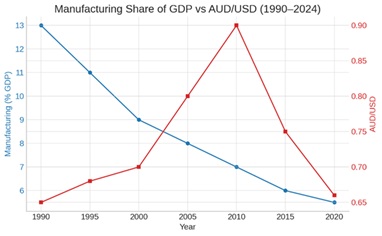

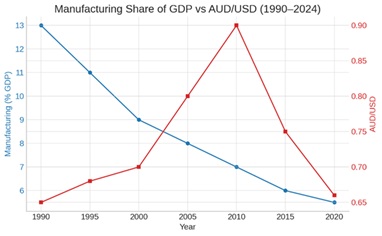

This capital round-tripping—where compulsory domestic savings flow offshore then return as income—mimics the resource boom’s currency effects. The AUD has traded structurally higher post-2000, averaging USD 0.75 compared to USD 0.65 in the 1990s. While commodity prices explain part of this appreciation, persistent superannuation-driven capital flows provide an underlying structural bid.

The Manufacturing Hollowing

Australia’s manufacturing sector has contracted dramatically, falling from 13% of GDP in 1990 to just 5.5% in 2024. Employment in manufacturing has declined from 1.3 million workers in 1990 to approximately 900,000 today, despite population growth of 60% over this period.

The elevated currency makes Australian-produced goods internationally uncompetitive. A persistently strong AUD, supported by both commodity exports and superannuation-driven capital dynamics, functions as a tax on exporters and a subsidy to importers. Tradeable goods sectors cannot compete when labour costs remain high in AUD terms but translate to uncompetitive rates in foreign currency. Fortunately, the AUD has recently been trading at the relatively subdued level around US$0.66.

Meanwhile, superannuation funds themselves show minimal appetite for direct manufacturing investment. Less than 2% of superannuation assets flow toward direct private equity or venture capital in domestic industrial enterprises. Instead, capital clusters in financial services, property, infrastructure monopolies, and offshore markets—sectors either shielded from international competition or benefiting from the very currency strength undermining manufacturers.

Conclusion: A Self-Reinforcing Cycle

Australia’s superannuation system, while achieving its retirement adequacy objectives, may indeed be inducing Dutch Disease dynamics. The mandated accumulation of $3.9 trillion creates structural market distortions: inflated domestic equity valuations, persistent currency appreciation, and capital starvation for internationally exposed manufacturing. Like natural resource wealth, excessive financial asset accumulation can hollow out productive tradeable sectors, leaving the economy dangerously specialized and vulnerable to financial market corrections.

The irony is profound: a system designed to secure Australians’ futures may be systematically dismantling the economic diversity necessary for long-term prosperity.