Quick Bite – What can we learn from South America?

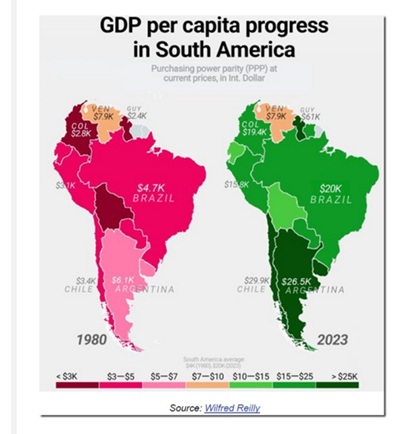

I came across a fascinating chart (shared below): it shows the change in GDP per capita across South American countries during the 43 year period from 1980 to 2023. The GDP per capita bands are colour coded, making the chart easy to understand at a glance.

Take Brazil, the biggest country in the continent. In 1980, its GDP per capita was $4.7k (pink); by 2023, that had grown to $20k (in green, and more than 4x higher). Argentina has also had a 4x increase, Colombia has increased GDP per capita by 7x, Chile by 8x, and Guyana a staggering 25x increase.

(Guyana is an outlier, and a consequence of the discovery and exploitation of massive offshore oil reserves, transforming it from one of the poorest nations in the region to the richest. But Guyana is tiny and has a population under 1 million, so not important for our purposes.)

Source: Mauldin, Wilfred Reilly

Only one country has stayed the same light brown colour: Venezuela, in the north of the continent. According to the chart, GDP per capita in Venezuela was $7.9k in 1980, and $7.9k some 43 years later in 2023. Venezuela is a country with a population larger than Australia’s (30 million), and is thought to have amongst the largest oil reserves in the world (in 1929 Venezuela exported more oil than any other country). It should have been a leader in the growth of its economy and in its wealth. What went so badly wrong?

Politics. Since 1958, Venezuela has had a series of governments, many authoritarian or military in nature. Economic shocks in the 1980s led to several political crises, including deadly riots in 1989, two attempted coups in 1992, and the impeachment of the president in 1993. A collapse in confidence saw the 1998 election of Hugo Chávez.

The new Chavez government introduced populist and socialist changes in the economy of the country, including nationalization of key industries, huge expansion of social programs, and strong rhetoric against liberalism and imperialism. All of which ultimately resulted in a socio-economic crisis that began under Chavez and continued under his successor, Nicolás Maduro.

The crisis has been characterised by hyperinflation, escalating famine, disease, crime, and mortality, leading to massive emigration from the country. Approximately 7.9 million people have migrated from Venezuela, making it one of the largest external displacement crises in the world (according to UNHCR).

The far left socialist policies of first Chavez and then Maduro have crippled their economy for decades. Venezuela did not experience any depletion of its vast oil reserves, only the mismanagement of the industry caused the decline in production – a mix of politicization, corruption and ineptitude. If ever there was an experiment in how damaging far left authoritarian policies can be compared with democratic liberal capitalism – this is a good example. Vast wealth turned to dust.

General observations about the region

Most of South America experienced strong economic growth in the early 2000s, driven by high commodity prices, but this was followed by slower growth and economic crises, including the 2008 GFC and more recently, the pandemic. Similar in some respects to Australia, the region’s economies are heavily reliant on the export of natural resources, making them vulnerable to fluctuations in global commodity prices.

Unfortunately, the region has been plagued by very poor political governance across many of its countries, and high inflation, unsustainable public spending, and volatile monetary policies have been persistent challenges. Income inequality – an inheritance of Spanish colonialism across parts of the continent – remains an issue, contributing to social unrest and political instability.

In more recent years, the rise of China as a major economic player in the region has altered the geopolitical landscape, leading to new dynamics in trade and investment. But there are also warnings of new “debt traps” that China may be sowing for many of these economies.

One bright spot is Argentina, a basket case for decades but now reviving strongly under the maverick leadership of Javier Milei.

Source: Getty Images

I don’t have space to go into any detail about the transformation that Milei is driving, but I can refer you to historian Niall Ferguson’s excellent piece titled “Milei’s Man-made Miracle” which was published on 22 July 2025. It is well worth reading, and shows that sensible and market-friendly policies can either boost your economy or bankrupt it. I’ll leave you with a brief quote from Ferguson’s article:

“After less than 20 months, Milei has eliminated the fiscal deficit, cutting it from 5 percent of GDP to zero. He has reduced the number of government ministries from 18 to 8. (“Ministry of Tourism and Sports—out!” he declared in a campaign video, tearing its name off a whiteboard. “Ministry of Culture—out! Ministry of the Environment and Sustainable Development—out! Ministry of Women, Gender, and Diversity—out! Ministry of Public Works—out, even if you resist!”) With Executive Order 70, issued a few days after his inauguration, he deregulated key markets, including property rentals, commercial airlines, and road freight transport. Labor market reforms took longer but were enacted after a fight in Congress.”

Extract from Niall Ferguson, Milei’s Man-made Miracle, published on The Free Press, 22 July 2025.